Director: Nicholas Ray / Year: 1956 / Color / English Language / MPA rating: Approved / Runtime: 95 min

In retrospect, it’s remarkable that a major studio like Fox released a film as brutal and intense in its depiction of suburban despair as Nicholas Ray’s long-lost, little-seen 1956 masterpiece Bigger Than Life. At the height of the Eisenhower era, Ray’s film didn’t just paint an unrelentingly bleak portrait of a single unassailable American institution, it put a malevolent spin on nearly all of them. Family, childhood, fatherhood, the suburbs, capitalism, school, community, church, friendship, home, and marriage all take on a nightmarish quality when filtered through Ray’s unsparing lens. In Bigger Than Life, the average suburban home becomes a haunted house, and a devoted family man devolves into a cross between a deranged cult leader and Mr. Hyde.

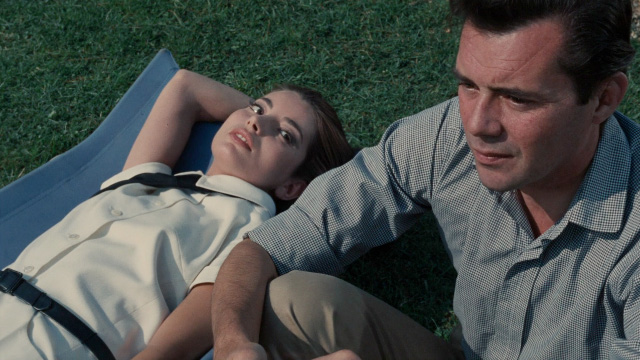

In a performance that makes his later turn as a debonair pedophile in Lolita look like bobbysoxer-friendly froth by comparison, a frighteningly committed James Mason stars as a teacher who moonlights as a taxi dispatcher in a desperate attempt to provide for his family and subsidize his sad little stab at the American dream. When Mason develops a life-threatening illness, doctors prescribe a new wonder drug called cortisone. Freed from the shadow of death, Mason becomes a new man—healthy, vigorous, and unencumbered by the insecurities that plagued him before. But his newfound bravado quickly takes on a troubling edge as he develops megalomaniacal qualities and transforms his once-sedate home into a dictatorship, and then into something much more ominous.

Mason’s descent into madness and almost unfathomable cruelty is medically and pharmacologically induced, but Ray and his screenwriters (the script includes uncredited contributions from himself; Mason, who also produced; and Clifford Odets) subversively posit it as an outgrowth of the character’s relatable desire to escape the dull, small-minded emptiness of suburbia. In his bid to escape the ordinary and prolong his life, Mason becomes monstrous, but never inhuman. In its harrowing third act, Ray invests his terrifying tale of upward mobility gone horribly awry with the sinister shadows and ominous atmosphere of German Expressionist horror films. Bigger Than Life ultimately pulls back from the abyss, but the ending only qualifies as happy for those willing to ignore the abundant darkness at the edge of the frame.

Review by Nathan Rabin for A.V.Club